SDG1 (No poverty)

Tag/topic

Latest content

Educating and Financing the Poor: Credit Union Promotion Club

This is a project located in #Malaysia.

Related SDGs:

- #SDG1 (No poverty)

- #SDG2 (Zero hunger)

- #SDG4 (Quality education)

- #SDG8 (Decent work and economic growth)

Data collection methods: Interview

Updated since: 2014

Background

The Credit Union Promotion Club (CUPC) was founded in the 1970s and registered under the Society’s Act in 1974. It was initiated by some community leaders who wanted to use a financial entry point to help the poor and needy within their communities. The main function of the CUPC is to establish and support credit unions, which are non-profit co-operatives that provide financial services to their members, by linking savers and borrowers in the same community. Credit unions pool the funds of members to provide capital and do not rely on external funding. The non-profit nature of the co-operatives enables the members to have higher returns on their savings and lower interest rates for their loans, as well as less fees to pay.

The CUPC provides education and training programmes related to co-operative administration, management and financing. It provides a platform for like-minded co-operative organisers (mostly from churches and NGOs) to discuss issues faced by their co-operatives, and to network with registered credit and other co-operatives. The CUPC plays a role to help co-operative leaders to understand globalisation processes and their impacts on local co-operatives and communities. It also acts as an internal monitor and evaluator for co-operatives within the Club.

The CUPC also does pre-credit union organising work, targeting the urban and rural poor, including plantation workers, indigenous communities, squatter communities, factory and industrial manual workers, land settlers, flat dwellers, small business owners, drop out youths, as well as single mothers and widows. Credit unions are important for the poorest 40% of the nation because they lack the access to financial services and social mobility. The CUPC aims for holistic human development of the community, through financial intermediation. The three-pronged approach used is: 1) eradication of poverty, 2) eradication of ignorance, and 3) empowerment of local leadership. Credit union promoters go to poor communities and understand the problems faced, and provide them with support and educate them through non-formal curricula.

Some facts and figures (numbers as of 31 December 2013):

- Number of credit unions organised –502

- Total membership – 49,079

- Children’s membership – 34,000

- Monthly savings – RM57,148,819.03

- Special savings (including children’s savings) for 2013 – RM17,740,962.58

- Profit for 2013 (of 502 credit unions) – RM4,603,278.04

Philosophy/Values/Traditional knowledge

The concept of credit unions was brought into Malaysia by a Jesuit-run organisation, the Social Economic Life in Asia (SELA), in the year 1966. It was then picked up by social workers and priests from the Catholic Church in Malaysia, which then sent some students abroad to learn about the concepts and implementation of credit unions. Besides its Catholic Christian roots, the CUPC is inspired by several different strands of ideology, including Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Antigonish principles, and the principles of cooperatives as stipulated by the International Cooperative Alliance.

Organisational model

CUPC is a registered society in Malaysia.

Sustainability from the Triple Bottom Line

Environmental Sustainability:

- The environmental impact of the CUPC’s activities mainly centres on environmental education. Among topics covered are water and energy conservation, the importance of organic farming and traditional natural remedies, as well as problems of plastic pollution and mass deforestation.

- The CUPC also adapts lessons from “Sittars” in India, explaining that air, water, sky, earth, as well as flora and fauna exist not only in nature but also in human beings.

- As part of their work with indigenous co-operatives, CUPC spearheads studies of indigenous knowledge on preserving nature and using medicinal plants.

- It also works on protecting customary land rights and fighting against land grabbing by introducing land mapping.

Social sustainability:

- The focus of CUPC is poverty alleviation and community empowerment through providing funding, education and opportunities to the poor and marginalised. Through identifying vulnerable communities and propagating the adoption of credit unions, the CUPC’s outreach team builds trust with the underprivileged and provides them with skills and knowledge to lift themselves out of debilitating circumstances.

- The education programmes provided include practical skills (e.g. accounting and business development), values and mind set shift (e.g. self-reliance), and understanding of structural issues that form their circumstances (e.g. globalisation).

- An important part of organising credit unions is the community-building that also happens in the process, which is instrumental in creating social capital and lifting communities out of poverty. The financial services provided to the community, such as insurance and small loans, also acts as a social safety net.

Economic sustainability:

- The operation costs of the CUPC are kept low. Various sources of income include training and consultancy fees, membership fees, interest from credit unions, etc. Fixed costs are low because the offices are owned by the organisation, and many of the credit union leaders work as volunteers or are compensated modestly.

- The registered credit co-operatives are also now making enough of profit to manage and administer themselves, owning their own buildings, paying their own staff, covering all administrative expenses and conducting in-house training programmes.

Challenges

- The main challenge faced by the CUPC is the demographic shift of the poor in the country. While it used to focus on the rural poor, urban poverty has become the norm rather than the exception. The main difference between the “old poor” and the “new poor” is the disintegration of communities in urban areas, leaving no social support for the vulnerable. What was done in the past was to engage the whole community to solve social problems and to establish credit unions; however in urban areas of scattered nuclear families, trust-building becomes a much harder process. As urbanisation speeds up, the types of social problems faced also become increasingly complicated, such as alcoholism, gangsterism, prostitution, violence against women and so on. As such, CUPC has had to revise their training programmes to adapt to the changing circumstances.

Featured image: Paul Sinnappan, CUPC’s founder speaking at a conference for social change via businesses for Christians. Picture Credit: ChristianityMalaysia.com

- Post

- Link

- Project

- as Link

- Event

- as Link

SDG1: No poverty

- By 2030, reduce at least by half the proportion of men, women and children of all ages living in poverty in all its dimensions according to national definitions

- Implement nationally appropriate social protection systems and measures for all, including floors, and by 2030 achieve substantial coverage of the poor and the vulnerable

- By 2030, ensure that all men and women, in particular the poor and the vulnerable, have equal rights to economic resources, as well as access to basic services, ownership and control over land and other forms of property, inheritance, natural resources, appropriate new technology and financial services, including microfinance

- By 2030, build the resilience of the poor and those in vulnerable situations and reduce their exposure and vulnerability to climate-related extreme events and other economic, social and environmental shocks and disasters

- Ensure significant mobilization of resources from a variety of sources, including through enhanced development cooperation, in order to provide adequate and predictable means for developing countries, in particular least developed countries, to implement programmes and policies to end poverty in all its dimensions

- Create sound policy frameworks at the national, regional and international levels, based on pro-poor and gender-sensitive development strategies, to support accelerated investment in poverty eradication actions

Barry’s Place – Ecolodge on Ataúro Island

This is a project located in #TimorLeste.

Related SDGs:

- #SDG1 (No poverty)

- #SDG2 (Zero hunger)

- #SDG5 (Gender equality)

- #SDG6 (Clean water and sanitation)

- #SDG8 (Decent work and economic growth)

- #SDG15 (Life on land)

Data collection methods: Field visit, interview

Updated since: August 2016

Case study

Background:

Barry’s Place is an ecolodge located on Ataúro Island, Timor Leste. The hotel is a family business, run by Barry and Lina Hinton. This permaculture-based social enterprise has been running for 12 years, and is an important connection hub for all the other social enterprises and NGO-run projects on the island.

Ataúro Island is located 35km away from Dili, the capital of Timor Leste, and is populated by approximately 10,000 inhabitants. Unemployment among the island dwellers is high, with the main work being subsistence farming and fishing. However, of recent years, there is a thriving SSE community on the island, including:

- Boneca de Ataúro, a women’s co-op which employs about 60 women, manufacturing and selling embroidered dolls, bags and educational toys

- Biajoia de Ataúro, a hearing-impaired co-op which makes and sells jewelry from local materials

- Empreza Di’ak, an NGO which works on business development in areas such as agriculture, poultry-farming, fishing, handicrafts, and tourism for the poor, particularly youth and vulnerable women

- Blue Ventures Conservation, a conservation ecotourism social enterprise, providing volunteer expeditions to generate income for local communities

Barry’s Place is an economic hub on Ataúro. Not only does it only hire local people, it also provides a marketing channel for the other SSE organisations, by giving their information in its website, its guest information book, as well as in the form of travel advice to guests at the reception. As Ataúro does not have many hotels, many tourists come through Barry’s Place when they visit the island. Besides that, Barry’s Place is the connection link between the locals and foreigners who want to implement community projects, in clarifying the needs of the locals and the expectations of the donors.

Philosophy/Values/Traditional knowledge

The owners of Barry’s Place have a strong commitment to ethical tourism and community development. They aim to provide assistance to the community in a way that builds on the richness and strengths of the community’s way of life, without creating a mentality of welfare or aid dependency. The permaculture philosophy adopted also forms a worldview of working with nature, rather than against nature.

Organisational model

Barry’s Place is a business owned by Barry Hinton and his family, and employs about 28 staff. On the website of Barry’s Place, it is stated that the ecolodge is a social enterprise, defined as “a revenue generating business with primary social objectives (human and environmental well-being) whose surpluses are reinvested for that purpose in the business or in the community, rather than being driven by the need to deliver profit to external shareholders and owners”.

Triple Bottomline

Social sustainability:

- Hiring local people from the island: Out of all the 28 employees of the establishment, all are local; Barry’s Place also provides them work year round, even when it is low season and there is no need for workers.

- Supporting community projects: A long list of community projects is listed in the website of Barry’s Place: the projects include linking foreign aid to local initiatives, building infrastructure, financial donations for educational and cultural activities, awareness campaigns on issues such as water and permaculture.

- Supporting women’s activities: The co-owner of Barry’s Place, Lina Hinton, participates actively in the “Feto Atauro” (women of Atauro) initiative which aims to build the capacity and potential of local Atauro women through forming Village (Suco) networks to disseminate information, facilitate training, and liaise with guest speakers and dignitaries. Barry’s Place also organises regular Zumba dance activities to promote women’s health.

Environmental sustainability:

- Eco-friendly design of hotel: The environmental sustainability of Barry’s Place lies mainly in the design of the ecolodge. Compost toilets and solar panels are installed; the chalets are also built with eco-friendly principles that ensure that they are comfortable to stay in without consuming a lot of energy. Barry’s Place also experiments with permacultural projects such as aquaculture rearing ducks and fish, as well as growing organic vegetables.

- Raising environmental awareness through leading by example: The eco-friendly building designs such as the compost toilets have been emulated by the villagers on the island.

Economic sustainability:

- Financially sustainable: Barry’s Place is financially sustainable, with good reviews from tourists who have stayed in their ecolodge. It also caters food for day-trippers and volunteer expeditions that come through the island.

- The ecolodge has also become an epicentre of economic activity, generating jobs for tuk-tuk drivers, housekeepers, builders, tour guides, fishermen, farmers, kiosk owners, bakers, etc. on the island. Visitors to the lodge also help support the local shops and co-operatives on the island.

Challenges

The challenges as highlighted during an interview with Barry Hinton, the owner of Barry’s Place, are as follows:

- Lack of general infrastructure: On the island, there is still a lack of general infrastructure. Waste management is done through bury and burn, and there is a lack of fresh water. Electricity by the grid is available only at certain hours.

- Low capacity in local workers: It is mentioned that the capacity of the workers is a problem as most of the locals have a lower level of education as well as no background in hospitality services. The decision to hire local also means that training has to be done from ground up.

- Lack of support by the government: The focus of the government in development is on mega projects, and this does not translate into policy directions that are beneficial for smaller hotels like Barry’s Place. Ataúro is part of the Special Zone of Social Market Economy (ZEESM) of Oecussi Ambeno and Atauro, which translates to a focus on high end transportation options like helipads and five-star hotels. The high level of red tape involved in doing business and paying taxes is also prohibitive to small businesses.

- Politicking among locals: The tight-knit nature of the Timorese society also translates to jealousy among families and businesses. Although this is the case, the fact that Barry’s family is not entirely local (Barry is Australian and his Timorese wife is from mainland Timor) sometimes work to their favour, as decisions can be made independently without having to succumb to nepotism.

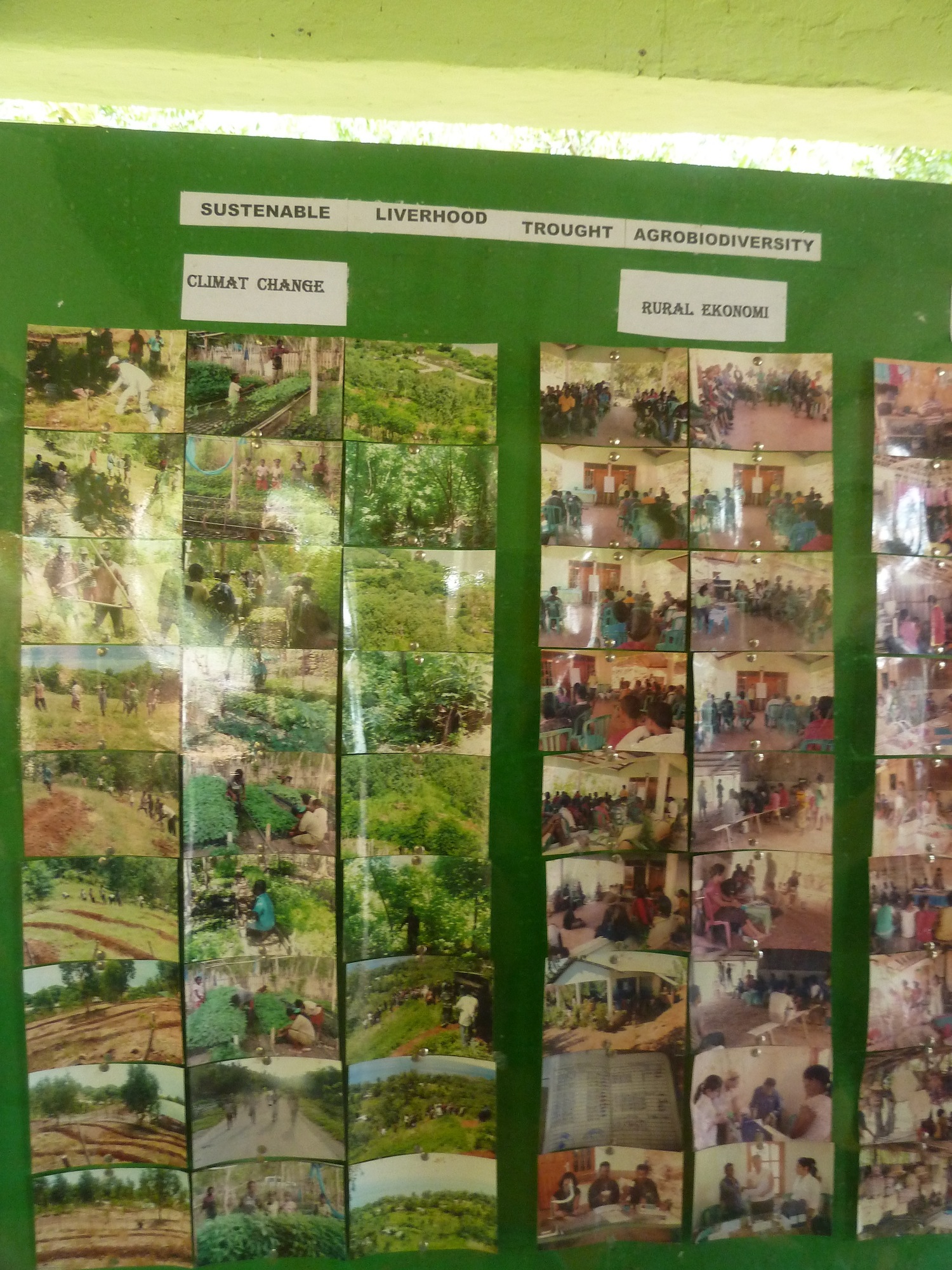

KIKA Community Agro-Biodiversity Resource and Learning Centre

This is a project located in #TimorLeste.

Related SDGs:

- #SDG1 (No poverty)

- #SDG2 (Zero hunger)

- #SDG3 (Good health and well being)

- #SDG5 (Gender equality)

- #SDG8 (Decent work and economic growth)

- #SDG13 (Climate action)

- #SDG15 (Life on land)

Location: Manatuto, Timor Leste

Data collection methods: Field visit, interview

Updated since: August 2016

Background:

The Centre is a collaborative effort between RAEBIA and a farmers’ co-operative, Ilimanuk. It has been running since 2012. The Centre serves 87 resettled indigenous families to increase their capacity in converting their livelihood from hunting-gathering and collecting fire wood to sustainable agriculture.

The approaches taken by the Centre include reforestation, introducing crop varieties, soil conservation, composting, creating terraces, restoring traditional village regulation of tara bandu (which protects everything that gives life, and is elaborated below). The 2.3 hectares of land that it is on was originally barren, able only to support the growth of eucalyptus trees and grass. This was compounded by the fact that the indigenous people were gathering firewood in an unsustainable way.

Besides their grassroots movement, RAEBIA also works on advocacy in the region and in Portuguese-speaking countries against the big agro companies that push for industry farming practices. They work closely with the government to implement projects from aid funding, and exert influence in what sorts of projects to accept. RAEBIA insists on agroecology and lobbies against farming practices that are unsustainable, including projects with hybrid seeds and chemical input.

Philosophy/Values/Traditional knowledge:

RAEBIA has facilitated more than 10 villages in performing participatory land use planning (PLUP). They help villagers to understand what the land use plan is, and the future plans as well. This information is then put into the village regulations. The tara bandu ceremony then officiates the village regulations. During the inauguration of the village regulations, all power players are invited – including religious and traditional spiritual leaders, as well as government officials, to sign the village regulations so that it would be respected by all. This process enables the community to understand the importance of resources and resource management. The PLUP process takes about 3-4 months, to go to the household level to collect information on land use, and to solicit participation in land use management. Tara bandu is a Timorese tradition, applicable to not only the indigenous people but all Timorese people.

Organisational model:

RAEBIA serves as a facilitator and the farmers are key actors. RAEBIA itself is a registered society, with a board including the founder, the patron, the management, and two farmers. Annually it has a gathering of farmers to provide feedback and comments in what help they would like to get.

Triple Bottomline:

Social sustainability:

- Food security: the percentage of food that the villagers produce and consume (as opposed to food that they buy) has increased from 20% to 80% within the four years of operation of the Centre.

- The focus is on family farming, not commercial farming, focusing on self-reliance and empowerment as RAEBIA does not want the farmers to be mere workers.

- Women is a key thematic area, and RAEBIA makes sure that women’s involvement is there in farming, and food processing.

- The work of RAEBIA is connected to health, because food and nourishment is intimately connected to health. In terms of health, the co-operative also sets aside money to help its members in health problems.

- Healthy, strong and united communities are equipped with the knowledge and resilience to combat the effects of a harsh environment and the impacts of climate change.

Environmental sustainability:

- The techniques taught by RAEBIA follow principles of agroecology (i.e. organic, no GMOs, no chemical pesticides).

- RAEBIA serves as a seed bank, and a centre for experimentation for cultivation of crops.

- Through converting land use to sustainable agriculture from hunting and gathering, as well as chopping down of trees for firewood, the environment is conserved.

- RAEBIA promotes control grazing to minimise livestock impact on the environment.

Economic sustainability:

- The farmers grow crops, and established the farmers’ co-operative Ilimanuk to process their produce, in order to diversify the economy.

- Ilimanuk also has their own credit union, and livelihood opportunities for women, such as using sewing machines provided for tailoring, and selling fried fish.

Challenges

- Land ownership is a problem in Timor Leste because of its colonial history with the Portuguese and Indonesians leading to a lot of confusion with land titles. NGOs are now fighting for land reform. Even in the case where there are no land titles, the community recognises the land ownership of certain individuals out of inheritances. The 2.3 hectares used by the Center belongs to the King, and RAEBIA has had to negotiate for the usage of the land.

- Poor farming practices are challenging. Traditional free grazing is still in practice and is not sustainable. Slash and burn is also a problem, although this is not a traditional practice. Farmers are not so confident in their local knowledge of managing the land which does not involve slash and burn.

- Other environmental challenges include water scarcity and deforestation.

- There is also a “dependency mentality” of community members.